We Won't Need Saving

These words come to me in a country where 16-year-old Nex, of Oklahoma’s Choctaw Nation, won’t stay inside the cage that gender throws over human bodies, won’t assent to what can be done in gender’s name, becomes a they, and goes on hearing the thump of their head against the girls’ bathroom jagged tiles. Where three girls yank at Nex’s hair and bang their skull so that Nex seems to go out, when their eyes don’t reopen. Where not one high school official thinks to call an ambulance. Where, the next day, Nex hits their grandmother’s living room floor, from which they won’t stand up. Authorities rule this death a suicide, though the antihistamine and antidepressant mix in Nex’s body (usually) fails to kill. The story shuts down after a few weeks, goes out, dies, which is where too many believe Nex Benedict and their kind belong.

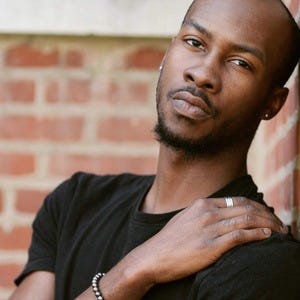

They come to me in this city where O’Shae Sibley and his friends are pumping gas, 11 PM all late July steam and grit around the station, its convenience store, in a Brooklyn hushed by heat. For a whole day they’ve jumped through waves in the only part of Jersey they can stomach. The car refueled, O’Shae sees how salt makes a second skin over the black body that’s been his for 28 years. Beyoncé’s “Break My Soul” booms from the stereo. Its percussive grind pushes into and supports the voice she lifts up on those two tiny words absent from her title, the “you won’t” that must carry more than their scale can say. “You won’t break my soul” in a world that equalizes spirit-stunting day jobs and the big leap of a life that can be prepared for, even when co-workers and lovers try to keep you little, so your arms can’t go wide. They’re voguing in a circle around the car in time with Beyoncé’s sonic love for 1990s drag balls and sparkly queens and the spine any Black man needs to lean into a dress, and that’s when the change begins. Outside the station’s ragbag of a store, white boys form a knot. Their shouts overlap in a slur, but stop that dancing now rings out. Fists thud on bone, O’Shae and his friends punch back, yet when the knife slides in, O’Shae’s a body on the ground. The high school student who killed him walks into a police precinct days later, because the surveillance footage he was unaware of means that he’d be found. After the memorial for O’Shae at the station where so many vogue and clutch flowers, after the white boy with a knife’s charged as an adult at 17: nothing. Any search engine yields a repetition of the murder, not what should follow it. And O’Shae’s just another story, twice disappeared.

They come in my writing classes at New York University, where the faces of Nex and O’Shae shimmer on a wall-sized LED screen and hold there.

We’ve been watching Simone de Beauvoir on the opposite screen talk about that punchy sentence from The Second Sex, the book that gave her death threats and belligerent phone calls and moneyed fame. It’s 1975: she looks directly at the camera while her interviewer reads, “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman,” clarifying that no female or male person can be totalized by the conditions of the sex into which they’ve been born. The individual and their culture interpret those conditions, so that the gendered categories of “woman” and “man” name how this interpretive labor pulls across a life. And that process takes time. You can concede to manifesting the sort of womanhood your environment demands—or not. You can have a penis and wear the pumps and the sequins that remind everyone around you how gender ought to be as capacious as the persons who imagine it. But risks trail the freedom in play here, and David Wojnarowicz wants us to stay with them. We look at One Day This Kid and its self-portrait of David at 8, his tooth-stuffed smile, joy beaming from his eyes. Yet an older David in 1990 encircles this boy with words describing the brutalities that will be his punishment when, in “one or two years,” he “desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.” Some like their gendered cages, like the fit, and will perpetrate whatever appears required to defend both. My students reflect in a shared online document on how these materials reach them in a world they’re starting to know, and most remember my advice: when you’re in trouble, make that trouble a part of the work, since your words sustain a dialogue with what struggles to stretch out towards you. But there’s a soft/sad relief at the end of Call Me by Your Name. Mr. Perlman acknowledges his son, Elio, stooped by losing Oliver’s love, the summer graduate assistant who’s left their Italian home, returning to America and the expected engagement he doesn’t know how to undo. Don’t run from this pain whose origin is the loving that still lives there, Mr. Perlman almost whispers, some students writing, I wish my father could care enough to hear those words.

Grant stands up after a few minutes, the one white male student at our table, and the room’s as if built for his rage.

He’s in his second week of college, like those he’s encouraged to call his peers, but nothing in this place allows him to turn back to what he knows. That enclave on Long Island’s North Shore, with its country club and private school, where everyone mirrors the standard that he is, whose rightness his past taught him to revere because it boxed likenesses in while locking differences out. He doesn’t understand how to feel any of it, the foreign-inflected voices, this university that won’t educate him by repeating the valued sameness he’d been instructed to believe will always be the single trait worth seeing. So he takes the six-and-a-half feet that the North Shore grew him into and looms, our table in his shadow. So air quakes in response to the threat in this voice that Grant pitches loud: everything I’ve brought into the room is not appropriate, I am inappropriate—and the peers he’s never talked to agree. Grant doesn’t notice the students below him gaze in wonderment at the assumption that he might lead the ones he’s so far disregarded. He doesn’t notice my asking him to recall: he’s been free to write about his troubles with our materials, but those troubles are his own. They don’t equal the texts themselves. Grant’s now the slap of the door behind him that shuts out with ease what becomes invisible through his inattention.

But there’s no easiness here, especially when the thing you decide to unsee and unhear talks back.

I’m at the men’s room sink on the floor where I teach. A day later, before class, I’m trying to work at quiet in my head, where ropes of words twitch and snap, not one of them my own. I know that “inappropriate” can be hitched to “unacceptable” and how the ones tossed into that outgroup should just shut up. Or be made to shut up. I estimate the community of people who deem themselves appropriate, the parents, grandparents, neighbors, the village, town, city, and country instructing a first-term college student in the verbal urgencies his lips must let out at the category of person who deserves denial, that acceptability shows his long-time teaching in action. Because what’s acceptable can only be right. I recognize the conceptual tie between numbers and rightness, that their cording together points you to what’s good. And I know that the question, but good for whom?, will always be redundant.

He slides his bulk sideways through the bathroom door, this security guard who eyes me down, up, whose copy I find in the mirror. He’s about to ask, with the easy menace his uniform permits: you know this is the men’s bathroom, right? I scourge him with curses about being a faculty member and a man and how he needs to rethink what he does with his mouth. I hear his sloppy aim at the urinals in the back. Before he and his bulk slide out, I get another examination, up, down, as I imagine the guard menacing a freshman, who won’t be able to move his feet. I submit a report to the university’s bias office because of that image. After three months, a supervisor emails: security staff will receive more training in how to deal with persons who have a fluid approach to gender. My reply, that without evidence, I have no certainty this training will occur, remains unanswered.

And I’m the noise of a rebuke that never happened.

I’m tired of the inaudibility, the illegibility conferred on my kind, on us, by systems and institutions and people who want us scrubbed away, vaporized, dead. Power customarily proceeds by obliterating from view the bodies that won’t meet its imperatives. Our histories untaught, unrepresented: the project of (straight) replication here raises up a particular human standard whose perceived fitness can manifest the faculty of blotting out what refuses to be it. And our exhaustion’s been planned for, since it quickens the silencing, the vanishing process. But if what you read inaptly, or don’t read at all, stands before you, a future lives in that capacity to stand. I think of Deborah Levy’s Elsa in her recent novel, August Blue. With COVID replicating and adapting to keep alive, Elsa’s a concert pianist who steps back from her industry’s regimented sense of what a concert must be to matter. She and a female friend near the front door of Elsa’s Paris apartment building. They startle a man on the other side, who opens it first. Elsa recounts: “Fuck you, whores, he shouted, and then all the usual. We were queers, we were freaks, we were Jews, we were hags, we were mad. The same old composition.” Against that familiar catalogue, I want to tell a story.

I see two unacceptable men, talking at a restaurant table.

Douglas Harnden and I sit in a booth at Man Ray in lower Chelsea, long before it transforms into a series of delis, followed by one radiology center after another. This 1990 spring’s so early that it stuns the scrawny trees visible through the slit of a window across from me. Douglas faces the human life bunched around us. He likes to affirm that it continues, and I like to see what’s coming. We’re unacceptable because we go hot for men in a country where that sizzle endangers us by law. Where law upholds the now outdated claim that our heat’s a mental disorder, a neural misfiring. And we’re inappropriate, not proper, unfit for sight: Douglas buckling from three years with the virus that Reagan in his White House never mentioned but cheaply resourced, me in my platform boots and bone-white hair, lashes dusted with eyeshadow the color of a fern. I’m in all this—the boots, the hair, the lashes—because of my terror before the crowding dead glanced at by the news and because I worry about the benumbing bore most men’s clothing is, that uniformed ingroup. Our waiter draws us to prints by the restaurant’s namesake on every wall. The impoverished ones afforded remembrance by chemicals swished in a tray. But my head’s full of the woman that namesake couldn’t stop shooting and didn’t know how to let go of, the Lee Miller whose photographs these walls omit and who left him.

She approaches Guerlain’s Paris storefront that’s in the business of organizing desire through marketing you in the dress, jewels, scent that will win the pair of arms you think you want. Or so the advertising copy goes. It’s 1930, a cluster of years before the great flare, the land grab, the poison gas. Miller pictures her Exploding Hand as a forearm in a dolman sleeve, its brocade bell-shaped around the wrist. Her shiny nails touch the door handle. All the glass behind it convulses into sharpened rifts, and that’s what this woman is, the breaker of insufficiently life-giving things intent on the new that could flourish in their place. Douglas drops his spoon into the watercress soup he’s played at eating, the cane he now needs smacking Man Ray’s floor. He’s the body that every man went monkey-mad for across the five years I’ve known him. The lover I never quite slept with because his blood-roiling beauty would always push him elsewhere. I’m the friend, the family, who’s about to take him to New York Hospital for a medication-adjustment to address the nightly leg spasms that can’t let Douglas dream. I match the curtness of the nurses when they insist the pills won’t be ready for another week. And Douglas wonders how you manage a door that will cut you as you journey through it.

I’m the loving family before whom Douglas undresses in his bedroom. He shows me lesions in the form of continents that rise up on every inch of skin, from the waist down. I rub them with pine oil to shush their throbbing. Close to sleep, we’ll breathe at the same time. For a while.

In 2024, I want to spot a drone heave into the sky. Its lenses won’t angle down on the present but range over a future finer than the one that numbers of us scheme to make. Nex and O’Shae survive the horrors designed for their ruin. They’ll walk on turf and among lives enriched by their contributions to them. Douglas won’t die at 32, too early for the protease inhibitors whose invention means that this is a survivable disease, as my students assert on the few occasions when they can focus on the 80s and 90s, prehistorical because they weren’t there. No, he’ll live, growing into the Douglas who writes his book on that Buñuel gifted with slanting sight, each film visualizing how whatever we signify by “life” outpaces our pronouncements concerning it. Nex, O’Shae, Douglas, the upright ones alongside them: we won’t need saving, and that will be a new composition.